Wine is art

Can you look at a painting for an hour? Immerse yourself slowly in a glass of wine?

Note if your email cuts this: read the article in full on ellenwallace.substack.com

Forget canonised wines - this holiday, be seduced by a wine you like

Before the holidays, consider your wines. I don’t mean: start your shopping list. I mean: think about What you might drink and Why and in particular How. Ask if you can give one wine more time than usual. Consider forgetting that you want to impress others or yourself with that very special very expensive very old vintage bottle lurking in a dark corner. Give yourself the gift of knowing wine as art.

Tip: Opt for moderation instead of trendy abstinence or its extreme opposite, high-intensity drinking.

The What, at my house

At my house in the Swiss Alps on Christmas Eve we will open a bottle of 2018 Vin de Constance from winery Klein Constantia in South Africa. This is a sweet wine, not late harvest, that has been famous for centuries (Jane Austen and Napoleon liked it), but that’s not why we are drinking it. My husband and I tasted and were enchanted by earlier vintages while visiting his family in SA for Christmas 2019—his last, as it turned out. He died in an accident in December 2020, when all the world was worried about dying from Covid. We will raise a glass to Nick (maybe rereading our tribute to him) and to his happiness the day he first tasted Vin de Constance.

This will not be a sad toast. Nick and I visited wild Pearly Beach, then cozy Hermanus on the coast, before going to Klein Constantia (Cape Town) for a tour of the vineyards. My notebook was filled with questions and my mind laboured to memorize the answers as we grabbed the sides of the bouncing open jeep that December day. It was followed by a tasting session in the cozy cellar of this remarkable winery founded in 1685 (better for note-taking). From there we went to his nephew’s home in Stellenbosch and enjoyed the antics of children on Christmas Eve, then stood out in the garden after a braai (barbecue) on a cool summer night, for it’s the southern hemisphere. Nick sang along to Paul Simon, Diamonds on the Soles of Her Feet. No one objected that he was a bit off key.

A passing family of nine paused to carol for us, a capella Christmas songs with exquisite African harmonies. An ancient grandpa carried the deepest, richest notes, causing me to shiver at the sheer beauty of it, and I drew my shawl closer. At the end, as someone handed out warm cookies all around, he came up to me, as the oldest “A Ma”, took my hands in his and bowed. Nick’s smile, for family and his beloved Africa, was peace itself.

Vin de Constance will not be venerated or canonized for its cost or fame or history this 24 December, despite its reputation (Jamie Goode’s report on his 2018 visit helps you understand this part). While these wines can last decades, we’re having a wine that was bottled just three years ago. It will be fully appreciated because I plan to give it time and pay attention to the wine itself. I’ll look for the emotional message it sends.

The emotion I’m talking about runs deeper than my family story. Wine that is art shares a universal message. This wine is aged in new French oak and some acacia for three years, so I bought the 2018 after Nick’s death, in Switzerland, with a future family event in mind.

Klein Constantia—the tools, the skills, the art

From the first sip I’ll be looking for a thread from the growers and winemakers who, that year, took grapes into the cellar, 21 different batches of them harvested between January and April for varied acidity then sugar levels.

They began with a basic recipe, some thoughts on the “textbook” cold weather vintage and an idea—just as a painter has a sketch and palette and tubes of oil. And then creativity and self-questioning will have set in, as they blended while the juices fermented, then again as the wine matured. It’s a process I, as a fiction writer, recognize. We research, we have notes, outlines, we write and rewrite, then edit until it is just right. The result is the expression of a need to share a message through a medium. It’s the same artistic process whether the end result is a painting or novel, orchestral score or a wine.

I could rewrite Macbeth, changing a character here and a quote there. You and I could take those same Klein Constantia Muscat de Frontignon grapes, and make a wine following the technical specs, if we were skilled. We would not come up with the equivalents, just as that Mona Lisa poster in the Louvre gift shop will never pass for the real thing. We would be making copies that were pleasant but without feeling; all art can be copied and will give this result.

We will let the Vin de Constance 2018 wine do what art does, transmit the feelings of the artists who made it.

Does art have to be the work of one creative soul, rarely the case with wine? Of course not. Think of films that are more than money-grabbing movies. Think of operas, of Renaissance ceilings and commissioned triptyches such as Giotto’s 13th century Stefaneschi and, most likely, much of Shakespeare’s work.

If wine is art, what exactly is art

Can we truly call wine art, or is this an exaggeration, the kind of marketing inflation that is a trendy sales tool in the wine business?

Leo Tolstoy was a Russian writer famous for his fiction, but he also wrote essays, one of which has become a classic over the past 125 years. In What is Art? he writes, “whereas by words a man transmits his thoughts to another, by means of art he transmits his feelings …

Art is not, as the metaphysicians say, the manifestation of some mysterious idea of beauty or God … but it is a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings, and indispensable for the life and progress toward well-being of individuals and of humanity …

… We are accustomed to understand art to be only what we hear and see in theatres, concerts, and exhibitions, together with buildings, statues, poems, novels … all this is but the smallest part of the art by which we communicate with each other in life. All human life is filled with works of art of every kind—from cradlesong, jest, mimicry, the ornamentation of houses, dress, and utensils, up to church services, buildings, monuments, and triumphal processions. It is all artistic activity. So that by art, in the limited sense of the word, we do not mean all human activity transmitting feelings, but only that part which we for some reason select from it and to which we attach special importance.

“A means of union” (my emphasis above). When scientific studies measure the harm that alcohol can cause, including of course wine, I remind myself that, at its best, wine also does immeasurable good because it brings people together and not just because it is a lubricant. The trick is balance. I keep this in mind when the talk of abstinence grows too loud, just as I remember the cries of abomination and immorality that are raised when new and unfamiliar types of art appear.

In April I visited the Quai d’Orsay in Paris for a major exhibition on the history of Impressionism. Paintings that shocked and horrified the world when they appeared are now glorified, to the point where the show was too packed to be able to view most paintings and as many people had their backs to the art in order to take selfies than had their faces turned to the paintings to study them. Children on tricycles were herded through by parents photographing their children receiving an early cultural education. If this is what art does, maybe we should consider abstinence?

Finding the art in art

Start with a painting …

Some weeks ago the New York Times published a series on how to focus, as a challenge, Can you spend 10 minutes with one painting? It caught my eye because I’d been reading a collection of essays, Art Objects, by Jeanette Winterson, where she challenges us to spend one hour looking at a painting. Her 1992 book had made me wonder if I could do just that, in a public space, since I don’t have any Masterpieces hanging on my walls. Why would you bother, I hear you mutter. An hour? Winterson, before trying this, compared all art to a foreign city one has been dropped into “and we deceive ourselves when we think it familiar”. I would argue the same can be said of wine, all wine. You can memorize the guidebooks and read the fine print on the labels, but do you know it?

After spending an hour with a painting she wrote:

What has changed is my way of seeing. I am learning how to look at pictures. What has changed is my capacity of feeling. Art opens the heart.

Art takes time. To spend an hour looking at a painting is difficult. The public gallery experience is one that encourages art at a trot… [there is] the thick curtain of irrelevancies … Is the painting famous? Yes! … Is the painting Authority? … Who painted it? What do we know about his/her sexual practices …Where is the tea-room/toilet/gift shop.

In August the New York Times published comments from many of the 7,000-plus readers who had tried the 10-minute focus experiment. Increasing discomfort. Increasing distraction. Increasing invention (“I can make up stories about the characters on the canvas much as art-historians like to identify the people in Rembrandt’s The Night Watch.”). Increasing irritation. This is the list NY Times readers provided after their 10-minute viewings. What was striking about the comments is that they were all about the viewer as much as what was viewed. In fairness, the newspaper had asked them how they felt.

By then, I’d read Winterson’s comments on what we would find if we viewed a painting for an hour. The 10-minute views remarks added weight to Winterson’s:

Admire me is the sub-text of so much of our looking; the demand put on art that it should reflect the reality of the viewer. The true painting, in its stubborn independence, cannot do this, except coincidentally …

We are an odd people: We make it as difficult as possible for our artists to work honestly while they are alive; either we refuse them money or we ruin them with money; either we flatter them with unhelpful praise or wound them with unhelpful blame, and when they are too old, or too dead, or too beyond dispute to hinder any more, we canonize them, so that what was wild is tamed, what was objecting, becomes Authority. Canonizing pictures is one way of killing them. When the sense of familiarity becomes too great, history, popularity, association, all crowd in between the viewer and the picture and block it out. Not only pictures suffer like this, all the arts suffer like this.

How to kill art, including wine

“All the arts.” Read this again and replace paintings with wine. A recent article on Swiss wine by a writer who helicoptered in, as journalists call this, mentions Gantenbein, Donatsch and Chappaz wines up front, to give the author Authority and the reader that aha! moment of recognition of wines labelled iconic. The article isn’t about these wines, it’s just situating the reader among Swiss wines that have been canonized to create a framework for anything new to the reader. In the process, something is flattened, lost—what’s new will be compared to bucket lists, the 500 wines I have to drink before I die.

Once someone who is considered to be an Authority declares a wine, especially of a particular vintage, to be a great wine (and thousands of bottles are sold around the world and vintages are examined closely and compared so that the wine now has a History and becomes rare) the price climbs and the proud buyers/now owners boast of their ability to cellar it. And yet, that very fine wine was once a new idea, a creative venture, a work of art.

“The calling of the artist, in any medium, is to make it new”, writes Winterson, noting the new work doesn’t repudiate the past but rather reclaims it. As with a Picasso or Cezanne or Hodler, a good wine always has precursors, vines that were tended in a certain way that was once new and that is now accepted, grapes that were handled in a revolutionary manner that is now copied widely. In fairness to the three Swiss producers just named, all continue to produce beautiful wines, carefully studying the terroir and the vintage each year. Marie-Thérèse Chappaz (Authority, in the form of Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate, gave a Petite Arvine sweet wine of hers 100 points in 2023), in particular, has little patience with being called iconic and she pours her energy into routinely re-inventing and re-creating wines. This is indeed art.

It’s not necessarily easy to distinguish art versus a simply pleasing bottle of wine. Winemakers encourage us, rightly, to stop worrying about whether or not we know or understand a wine and to just let it please us. Their goal is to demystify the wine, to get us to relax and to have faith in our own taste. This is a good start, but we can take it further.

The same principles apply to paintings. I’ve gone to galleries and museums over the years and while I abhor bucket lists, especially for viewing art, I’ve often come away saying I loved it, I loved it not, I loved it—and so on through the entire show, quickly and without much thought. I would tell you I know little about art. But Winterson’s own experience convinced me to try spending an hour with one painting to see what I come away with, to understand why this particular piece of art has touched me.

Give it time

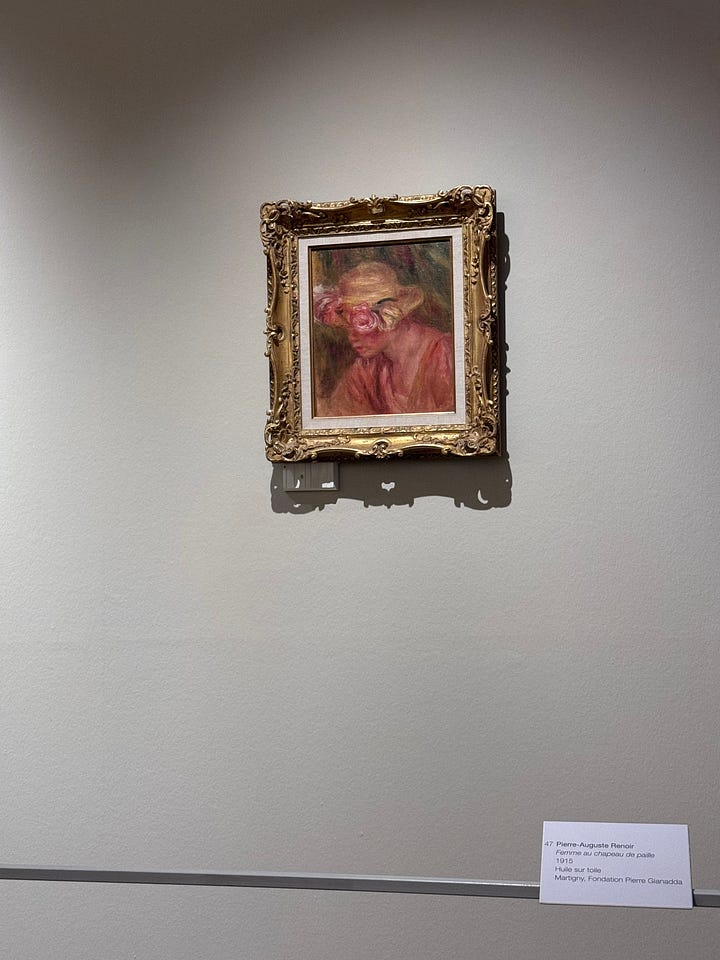

Art takes time, says Winterson. I allowed myself an October afternoon at the Gianadda Foundation in Martigny, Switzerland, for its show, Regards Croisés Cézanne Renoir, which closed 19 November. I thought I might need an hour just to find a painting I could look at for an hour, and I was right. The painting that caught my eye, that I returned to, was one of the last ones. I’d been considering an intriguing Cézanne, Le rocher rouge (the red rock), but my interest in it felt intellectual, a desire to dismantle the style and process.

Taking my cue from Winterson, I was looking for something that didn’t just please me—several of the paintings qualified there, for I like both of these artists—but something that made me pause, that made me feel … what? I didn’t know.

Just in case I didn’t last, I had a nice hike in the vineyards above Martigny as my reserve activity.

It turned out the hour was not difficult and it was memorable. Two details are worth noting because this works only if the conditions are right—something I’ll keep in mind for that Christmas Eve South African wine. The Gianadda is a favourite place of mine for viewing art because the crowds tend to be small and they are art-lovers who linger and discuss. I chose a day and time when there would be few people. It was easy to look without interruption. Most people, seeing me, stepped back so they wouldn’t block the painting. Secondly, next time I will take a lightweight folding stool. It hadn’t occurred to me that there are no chairs in front of paintings here. A kind employee, when I asked if I could borrow a chair from the auditorium, insisted on bringing it for me.

When I compare this experience with the Quai d’Orsay Impressionist show, I think of what it would be like to drink a rare 1950 Bordeaux at Harry’s Bar in Paris, while being jostled by men shouting orders for cocktails and women with too much perfume reaching across me for their retro ballons of Beaujolais Nouveau.

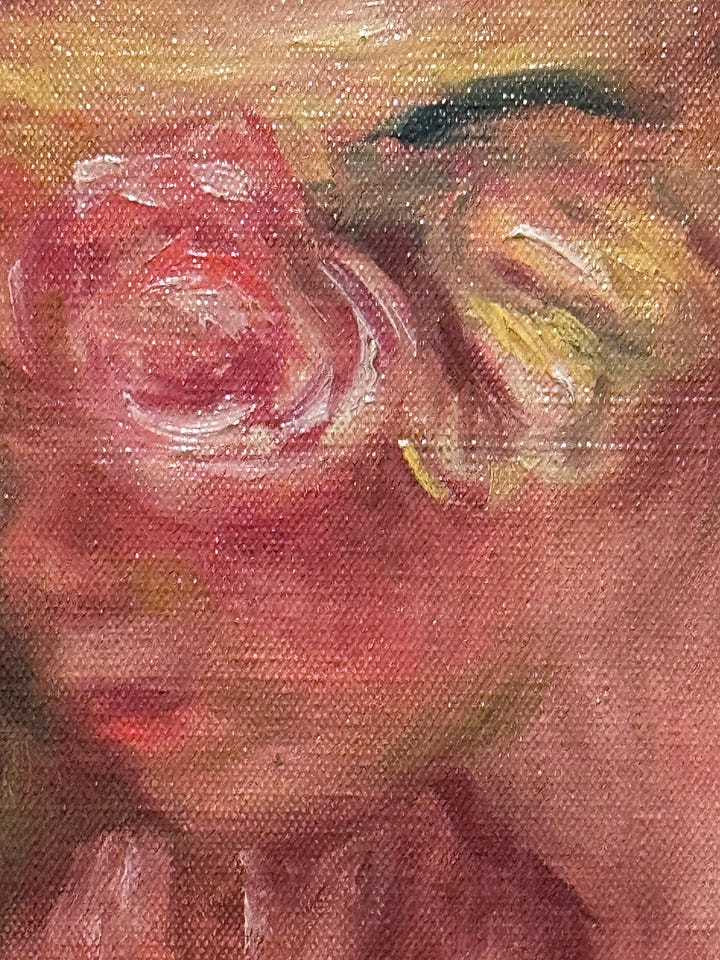

The painting I chose, Auguste Renoir’s Femme au chapeau de paille (Woman in a straw hat), was not the most famous or eye-catching. It was small, just 35x27cm. It took me a while to realize what had given me pause. I love hats and thought at first it was the broad-brimmed hat with its large and loose flowers, a classic for the period, 1915. But there were other hats, his wife in the garden in one (1905) and another from 1915-1919 that was larger and more luxurious. Then I decided maybe it was the colours, tones of pink and rose and russet and peach, all favourites of mine since the days when I was a red-headed child who was told I looked good in those colours.

But then I remembered Winterson’s negative comment about “the demand put on art that it should reflect the reality of the viewer”, so I stopped thinking or trying to understand why it appealed to me and I simply looked at it, without rules about how to do so except to stay focused. It dawned on me: this is the rare Renoir where we don’t see the face, remarkable for an artist known for his portraiture. It’s a closeup and yet the eyes are hidden. What, then, was I looking at? I walked up close and studied the paint strokes. I stepped back and the structure, the balance became more apparent. I sat down again and went adrift.

And finally I saw it. For several minutes more, I sat and felt tears rise and recede, as unformed phantom memories of my own came and went. There is one line, one stroke in particular, that is the essence of what moved me. The young woman’s mouth is barely open, the way we are when our breathing is shallow and we are distressed. But it is the jaw, the taut angle at which it is held, that speaks of grief. A death? A lover lost? An employer who chastised her? It doesn’t matter—the chagrin is seized, suspended, that fleeting moment of pure hurt, when deep sorrow catches us unaware. The beauty of his ability to capture that private yet universal drama made the clock disappear and I was startled as I handed back my chair to see that I had sat there for more than an hour, letting the painting lead me where it would. I can’t tell you what I thought about; I don’t know.

It was after I left the Gianadda that I read about the painting and I was not at all surprised to learn that 1915 was a very difficult year for the artist. His second son was critically injured in the war, his wife died, and he moved out to the garden to paint, fast and hard and with brush strokes that were forceful, at times almost violent. Grief is violent. The true artist, says Winterson, is after the problem, the false one after the solution. For Renoir, I’d wager the problem was how to express the purity of sheer unhinging loss.

… finish with a wine

Coming back to 2018 and Vin de Constance, I don’t know what the winemakers were seeking, only that it goes beyond terroir or weather that year or technology. These are winemaker’s tools, used with skills that have been honed. There is something else that they will not have identified until the wine was made. I can read this official description, and it is like the colours and hat of my Renoir, offering hints and only hints about something greater:

Bright and yellow gold in colour. The nose is layered with complex flavours of Seville marmalade, ginger spice and grapefruit. A rich and luxurious mouthfeel, the wine is full-bodied, fresh and vibrant. The palate is balanced showcasing a perfect harmony between salinity, acidity, spice and sweetness. Concentrated with suspended density, it concludes with a pithy astringency and a lingering finish.

The Why and the How of my wine

I chose this wine because I remembered that it was distinctively different from other South African wines or from late harvest sweet wines, at which Switzerland excels. That each vintage I tasted had something that made me fall in love a bit, blindly. Wine is a form of art that begs us to use all of our senses.

Wine is a form of art that begs us to use all of our senses.

How we will drink it: this wine is art, I am sure of it, and I want to understand why. We will put a small child to bed and then the rest of us will take a glass to sip, quietly, each in a comfortable corner, no cell phones or work or music, just a few minutes alone with the wine and silence in the hope of coming to the table to share one small thing about it. It might be a memory, such as a sea breeze or a childhood reading of 1001 Nights imagining Sheherazade’s jewels or a desire, to see the glory of the sun abruptly streak across a mountain peak. Maybe a vaguely sensuous longing to touch velvet or listen to Beethoven’s Fifth.

We’ll see what feelings reach us.

In any case, there will be some left to share, over conversation and dessert.

Ellen, this is one of the most gripping and beautifully written pieces on wine, and art, and human experience to come my way in a long time. I hope it will find the wide, wide audience it deserves. I will carry your thoughts and perspective with me into December and far beyond. Thank you!