The first slice sets the tone—big? little? tidy? symmetrical? The point squarely in the middle? The last slice is a statement about politeness and sharing. It all comes down to size, when you’re divvying up a pie, but there’s more to this than meets the hungry eye. And of course, first you have to bake the pie.

Saturday, early in the morning, I harvested rhubarb from my Alpine garden, marvelling at the deep pink of the stalks, striated with green. Spring comes late at this altitude, and rhubarb is our first taste of it. The harvest was twice what I had planned thanks to the ground being trampled on Thursday by gardeners trimming big trees after our 17 April epic snowfall of one metre in 24 hours. Too much rhubarb means just one thing: pie time.

I feel terribly sorry for anyone who does not love pie and very sorry for anyone who does not bake pies and sorry for anyone who thinks a pie without a homemade crust is really a pie. Because I love and bake and believe in pies, Saturday morning turned into a joyous occasion. I put Bach on in the kitchen, told my adult daughter Tara, who is quite handicapped (which is not an impediment to loving pie) that we were about to bake rhubarb pie. She quickly installed herself on the kitchen floor in anticipation. Every few minutes she needs to be reminded that from the gleam in her mother’s eye to the first bite of warm pie, there is a long waiting period. She watches my every move, and when the pie goes into the oven she watches over it while it bakes.

Sometimes it’s the shortening that triggers memories, or it might be the flour, but this time it was the pastry cutter. You cannot bake a pie without memories flooding the kitchen and your heart. This pastry cutter is a strange tool, all curved wires and a very worn once-green wooden handle. I have two others, modern and black with flat shiny surfaces where they cut. One is squarish with small square holes, the other round with circular ones. One is a potato masher, but I never remember which. In any event I mash with a fork.

One of my sisters gave me that pastry cutter last year, when I visited her in Nebraska. She is downsizing, slowly, as is everyone in their seventies. She remembered my pies. So before I brought it home to Switzerland we made pie crusts and put them in her freezer, to be used for Thanksgiving, and we reminisced about how we had all used that pastry cutter as children, so it must be as old as me.

I have three pastry cutters and an excess of just about everything for the kitchen because my husband Nick, who died in 2020, loved pies as much as he loved stocking a kitchen with tools. He liked to cook but more than that he liked to think about all the things you could cook and he had a kind of male love for mechanical objects. He never baked a pie in his life. He could hardly wait for mine to come out of the oven.

Pies are not necessarily in the genes. My Grandma Lonergan was the family’s famous baker, mainly of pies and a steady stream of fresh bread. The smell of her house was imprinted on me early, and drove my own love of baking. Yet, my mother, who grew up in that house, was a determinedly efficient housewife of the 1930s to 1950s era of big refrigerators and all other appliances, and Betty Crocker. If my mother ever baked a pie, I don’t remember it.

Favourite pie? It depends on the season although pumpkin from garden ones is right up there, and apple if you have perfect just-picked apples and the right spices, or cherry when the tree boughs are kissing the ground with their load of fruit. Then there’s the chocolate cream pie that in 1974 caused my non-cooking boss (her boyfriend was married, so no home-cooked meals called-for), at my first real job, to tell everyone I was a fantastic cook. I panicked in case someone suggested I cook a meal, and I started practicing from The Joy of Cooking.

Later, I lived in Paris where I over-ate individual lemon tarts on the basis that unlike American pies, French tarts don’t have top crusts, so they are nearly diet food. Thirty years later when I thanked my new Swiss neighbour for some help she’d given by taking her a pie, she rolled her eyes at the American excess of a top crust, but she did say later it was good.

So many people, so many pies! I once offered a fresh pie as a prize on the Swiss news website I published. The man who won it was unable to collect it, but we had a mutual acquaintance and when I asked him to give the pie to his friend the winner, he looked at me warily.

“He’s married, you know. Happily married.” Oh dear, the old pie as bait idea, and my explanation did little to convince him that I, too, was happily married and the pie was a prize.

It’s taken a long time to learn to be careful about making pies for men. The first apple pie I made for the first boyfriend prompted him to decide we would get married and I’d leave school and we’d have a passel of Catholic kids right away. I balked: in a fright (I was busy reading Susan Sontag and Betty Friedan and The Joy of Sex) I drank too much beer on a sunny May afternoon on campus and ending up making out for hours (remember those days? We thought they’d never end) as part of an anti-Vietnam college protest. A., the boyfriend, had a creepy roommate who passed by, went home and told poor A., who came by to see for himself. Sure enough there I was rolling on the grass with another guy. Despite his Siciliano blood he walked home quietly and waited for me to break up with him. It took me a week and a great deal of red-faced mumbling, unaware that he’d seen my crime. I saw him again ten years later and hoped he was as relieved as I was that we’d split, for we certainly went in different directions. I remembered his mother’s extraordinary homemade pasta, tomato paste and sausages, I said. He remembered my pie.

In the Swiss kitchen now I change the music, talk to my daughter, try to show her a photo of herself at age 10 where she is waiting for a pie to cool on the veranda. She isn’t interested in screens or pictures of her past, or pies that you can’t put in your mouth right now. Her eyes light up as I cut butter into little cubes.

Pies are first and foremost family affairs, and my mother loved my pies. Her favourite was always lemon meringue. In an unusual effort to please her I would so very carefully use a spatula to get the meringue just right, sealing the edges at the crust. Then I had a binge of making banana cream pies, and one sister loved those. If we are still speaking today, despite our differences over the American leadership, it might be because of those banana cream pies in our background, moments of love shared.

Rhubarb pie: technically, the rhubarb filling comes first because the fruit needs 15 minutes of being married to sugar to let go of its sharp tongue, before it can enter the sociable side of the pie: the crust. We’ve all known couples who are like this. Sugar on its own is too much sweetness, and who needs that, but rhubarb alone is also over the top, with its acidic character. This sounds like an argument in favour of marriage, suggesting that each benefits from and is improved by the other. I believe marriage only rarely does this, creates one better whole from two contrary parts, so no, pie is not an argument for wedded bliss. The history of pies nevertheless may well be tied to women trying to charm or hoodwink men into marrying them.

Rhubarb filling (various sources)

Mix together: 4 cups (about 480 g) of rhubarb stalks (ends trimmed off—cut into 1/2-inch/2.5 cm pieces) with 1.25-1.5 cups of sugar, 4 tablespoons flour and 1/4 teaspoon salt. Let sit for 15 minutes.

Consider this: I have known few men who bake pies from scratch, although James Beard famously loved them. In fact, try as I might, not a single such specimen comes to mind. As for hoodwinking, both men and women do this, but more often by being manipulative and pie is not a discreet enough tool for this.

The absence or presence or profusion of pies, if I think about it in relation to love affairs in my own life, offers a few lessons. I mull them over as I knead the dough. Kneading is akin to meditating, with a sensory edge and the promise of more of that to come.

Pie dough for a two-crust pie

2 cups white flour, 1 teaspoon salt, 2/3 cup chilled shortening (Crisco can’t be beat for this) plus 2 tablespoons chilled butter, 4-6 tablespoons water

The Joy of Cooking (20th century version) is the bible here: Cut half of the shortening into the flour until it’s like cornmeal, then the other half until it’s like small peas. Sprinkle the water, lifting with a fork until you can form two balls of very slightly sticky dough. In my dry climate, I often have to use 6 tablespoons of water.

After the Italian-American bowed out, I spent too much time making out with and no time baking for B., the new beau. We never quite hooked up, since he’d gone in a short time from being geeky with thick glasses and a shaved head (thank his dad for that), to a very sexy long-haired dope-smoking guy with contact lenses who played Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd. Girls fell over him. The next thing I knew he was marrying the cutest little blond on the block who did his laundry, cooked his meals and generally ensured he felt he couldn’t live without her.

Fast forward nearly 40 years, marriages in disarray. At long last, I baked him a pie. He was happy to eat it, but he was indifferent. “Indifferent” is a word I don’t use lightly here, for the opposite of love is not hate but indifference. “I’m not really a foodie,” he explained. Neither am I. But I do love pie and he didn’t. Sure enough, soon after, we both realized that we’d been leaning on each other in the wake of relationships that had ended, and we were able to shake hands and say farewell while remaining friends. He kindly doesn’t send digital rolling eye emojis if I send a photo of pie.

The art of rolling pie dough

You have to bake about 100 pies before you develop that special feeling that tells you the dough is just right for rolling. I can only encourage you to go for it. Form a ball that is firm enough to stick together and not dry. Using only the palms of your hands, not your fingers, gently flatten the ball into a circle about half the size of the bottom of the pie pan, on a lightly floured surface. Use a good, heavy rolling pin on a lightly floured surface. If you don’t have a heavy one, try using a full litre water bottle, preferably one without grooves. With quick, light movements, roll the dough out from the middle until the circle, now thin, is larger than the rim of the pie pan. It helps at the start to keep adding a sprinkling of flour to the surface so you can spin the dough before each rolling, to make sure it’s not sticking. I use a large, thin cooking spatula/flipper to loosen the dough gently, often sprinkling flour onto the spatula. Gently set the rolling pin down on one edge of the dough and ease the dough over it until the dough is dangling on either side of the rolling pin. Speed is essential here: get that dough into the pie pan now!

At this point in Saturday’s pie process I began to reflect on old friends, how we used to communicate by hand-written letters and we don’t any longer. A couple of years ago I opened a box of old letters, including those from the love of my life when I was in my 20s and early 30s, before I met my husband. Every time I began to feel comfortable and at home in the relationship he dumped me. His new girlfriend (our next door neighbour who left her husband for him) told him she wouldn’t let him “abandon” her, as he had me. He seemed impressed by her assessment of his relationship with me and that word abandoned. When he told me this, we were camping on a mountainside, and he was two-timing her to be with me (life was complicated then). I was too angry to tell him that “abandoned” was my word and description, not hers—she’d picked it up when, under the guise of wanting to be my best friend five years earlier she’d pumped me for information and intimate details about my relationship with him. Call it the One Who Got Away or think of it as lucky me, but here’s the point: I don’t recall ever baking him a pie, in the 10 years I knew him.

It’s rare to bake pies for people who don’t know how to at least appreciate you; maybe some innate pie-baking instinct spares us that error. More than 40 years later he still refuses to speak to me after one of those nasty and embarrassing romantic/friendship blowups.

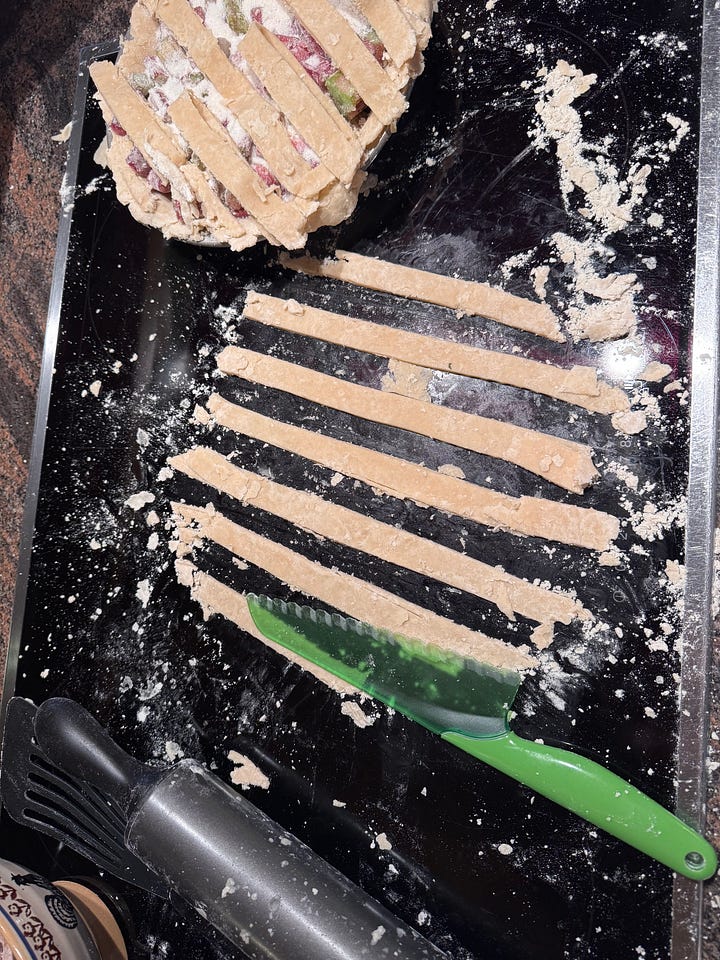

The lattice top crust

The best top for a rhubarb pie is lattice crust. It leaves room for the rhubarb to breathe while it bakes, the way people need to give each other room to breathe. Now this step gets tricky, at least the first time. I learned it quickly because the year I was seven or eight I received a small weaving loom kit for Christmas, complete with multi-coloured elastic cloth bands. The idea was to make potholders for the kitchen. I was soon spending my meagre allowance of nickels and dimes on more elastic bands, with blue and red particularly popular. That year my mother was never short of potholders and they made a bright display next to the oven.

You do a lattice top with the same potholder weave, alternating strips of over and under. Under and over. I remember early in my pie-baking career thinking that my love life felt like that. I met a man, W., in Paris and I was smitten, the only word for it. He seemed equally smitten. I took him to a small Montmartre restaurant and taught him to eat frog’s legs and we wandered home with arms around each other, misty rain obscuring city lights. When in Paris … when he was in Paris we talked about art and beauty and history and then he went back to America, before I understood that he had a wife in America—

I am now fluting the edge of my rhubarb pie, lattice crust neatly in place, and suddenly realise that I never baked a pie for him. We were too busy trying to be lovers under an inauspicious sky which, inevitably, was a sky that fell in. His wife learned of his deception and threw a fork at him that sent him to the hospital for stitches. Not, I believe, a fork for eating pie. Another marriage that didn’t last, but by then I was gone.

“Served him right,” said a close friend when I recounted the story, years later. She will eat any pie I bake, and it is she, Scottish, who pointed out to me that American pie crust has a pinch of salt that makes it special. He, meanwhile, is good to his second wife.

Baking the pie, cooling it

I nearly forget to dot the crust with butter. I have cannot eat dairy products thanks to a tick bite that sparked an alpha-gal allergy, but I cannot bake a fruit pie without using a tad of butter to make the flour and juice thicken. I resolve to eat just one slice.

Tara is getting impatient, and I slip the pie into the oven.

“Ten minutes at 200, then down to 180 for another 35 minutes,” I tell her. She knows this game. I no longer need to check my little chart for translating fahrenheit to metric, but it took me about 30 years to make the transition.

I resolve to think of pie in relation to women in my life while this one bakes, to avoid the trap of thinking that pies are circles of love we make mainly for men. They’re circular because they have no beginnings and no ends. I don’t remember the first pie I baked and I don’t believe I’ll remember the last one as such. I rather hope it will be key lime meringue. Or maybe pecan. Meanwhile, I bake for my daughter and after 15 minutes of cooling, despite its soupy look, we cut into the pie, that first slice and although she can’t speak, I do believe she’s telling me to make the slice a little larger. So I do.

Normally, pie should cool for an hour. Take the tip of a long knife and place it in the very centre of the pie. Cut deeply and slowly, from the centre to the edge. Lift the knife and repeat—making sure that the slice you’re cutting will be the perfect balance between crust and filling. This is a very personal decision: ignore voices that say “just a little piece for me.”

When my son, who lives in China, came home for the holidays I baked a pie, pecan with a dose of Iowa rye whiskey and molasses. It was eaten far too quickly, not because we kept cutting into it but because we all kept sneaking by to “just tidy the edges”. Pies are notoriously difficult to cut neatly, if they’re home-baked. At bedtime there was one small slice left and I decided that when I came down early to put on the kettle for the family I might make a small cup of tea for me and have pie before breakfast, the height of decadence. But when I pulled the pie pan out of the oven (where we always put “the rest”) in the morning I saw what qualifies as the world’s tiniest slice of pie. I was stumped. Then my son, preparing for an early morning meeting with people in China, crept into the kitchen looking sheepish.

“Oh, you’re up already.”

“Was this you?”

He nodded.

“Why did you leave this tiny, tiny scrap?”

“You always say to be polite and leave the last slice.”

True. He took his coffee and wandered off. My tea was ready. I stared at the pan and remembered my mother telling her four squabbling daughters to be polite and leave the last slice. The implication was that it was for my father and when he actually got the last slice he made a big deal of it—he understood his role. She was the maker and enforcer of rules, but he was to appear to star in that role (it makes me think of the US president now, and his gang of enforcers). She also used to bake and then hide cookies from us because we were not good at following the rules, until she had the brainstorm to hide the cookies in the washing machine. And then she forgot the chocolate chip cookies hiding in there when she washed a load of white clothes.

Should I bake another pie, I wondered, staring at the one pecan wrapped in a hint of crust.

Pies are circles within circles. No beginning and no end. The number of slices is finite of course, but the space between slices is infinite and the more pies you bake, the more love you share. My daughter and I will not finish the rhubarb pie, although despite my promises to myself I have two slices. The rest is taken to the group with whom she lives, for a Saturday afternoon treat. I explain that the American pie pan, ten inches with sloped sides, is precious and irreplaceable in Europe, and I’d like to take it home. Of course, says the man, who washes and dries it for me after carefully sliding the half of a pie onto a large plate for their “quatre-heures”, which all French-speaking schoolchildren know means an afternoon snack to give you the strength to get through the rest of the day.

I’m home, my daughter is with her friends, the pie pan is stowed in a cupboard in the basement, where I won’t be tempted to use it. Pies are nevertheless on my mind again and it’s only Monday, and I’m alone. I cannot bake another pie yet.

Who, I wonder, will need a pie sometime soon.

Shame about that old beau halfway around the world who still can’t speak to me or answer a Christmas letter after four decades—he could use a little sweetness in his life, I’d say. Some logistical issues, of course. But then I remember how my first clue that “we” would never make it was my suggestion in 1975 that we make a bowl of popcorn and he told me he never ate it because he was afraid he wouldn’t be able to control himself, and he’d eat too much. Cannot a whiff of excess be part of joy, to be balanced out the next day, I wondered? He was very fit, still is. Does he ever let himself eat pie?

A crumb of honesty is called for here. A tap on my own knuckles: what I’m really doing is saying I won’t take part in my own erasure, the silent treatment by someone who once meant a great deal to me. The New York Times (paywall) recently had an article about how unhealthy for everyone the silent treatment is:

… Some people think the silent treatment is a milder way of dealing with conflict, said Dr. Gail Saltz, clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

But it isn’t, she explained. “The silent treatment is a punishment,” she said, “whether you are acknowledging that to yourself or not.”…

…While using the silent treatment may give you a sense of power and control, Dr. Williams said, it’s also draining. It takes work to enforce “this behavior that’s unusual and contrary to norms,” he explained, “so it takes a lot of cognitive effort and a lot of emotional effort.”

It’s possible to move on in life but still remember the past and even keep it alive; where would we be as fiction writers if we didn’t understand that even where the past is someone’s undoing, its traces woven through the present are what can make people stronger.

Where are we as a society if we don’t acknowledge our past and allow it to survive in the present, adapting it with good grace to improve our world? Talking to each other to explore differences, without bullying noise—and also without bullying silence is the starting point. America, are you listening? There is no room for the silent treatment—in this case, political deafness—if you want the country to have a future.

I’m not entirely joking when I say town hall meetings with homemade pie might help.

I think of my mother and her frequent reminders to be humble. Humble pie. Lemon meringue for her, who could be sharp with this daughter who was too wild as a girl. She worried about eating too much bread but she would let herself go for a large slice of good pie. I took her out for a cup of tea and a little lemon tartelette in Paris in the 1980s, then baked her one of my own pies: hands down, mine won her over. We disagreed sharply over religion, but four years later, when I married, the wedding was in a Catholic church out of consideration for her. I got more out of that act of generosity on my part than it cost me to make it.

I think of her mother. Grandma’s apple pies came steaming hot out of a black iron stove with a pipe that ran up through the ceiling, pies that we knew were made just for us, and it reminds me that I carry her middle name, Genevieve, which when I was little seemed exotic. It still carries a special something—lessons in generosity?—for me. How had Irish immigrants given her a French name and who, in that family, taught her to bake pies? I remember my mother telling me stories about growing up in that small town in Iowa, surrounded by large farms owned by German immigrants who worked so hard from sun-up to sun-down that they ate six meals a day, and they had pie, always at least two varieties, for at least two of those meals. Maybe she told us those stories to motivate us to work hard: the reward might be endless pies when we visited Grandma, who was most decidedly not of German stock, but shared a belief in pies with those fellow citizens with whom she disagreed about so many other things.

My thoughts go to my father and his love of gooseberry pies and I run outside to check on the wild gooseberry bush I planted in his honour. Last year was its second year and I had enough gooseberries for one pie. Friends from America visited one summer and C. was so excited by my Iowa recipe gooseberry pie that he had three slices (now, there’s a young guy who’s buff and can afford three). This year, it looks like maybe there will be two pies.

It’s time to check on the blueberry bushes and yes, they are coming along nicely, although I beg them to be more prolific. Next year, they nod.

I add a blueberry pie to a chapter of my just-completed novel, which I am revising:

Edward was baffled by this new Mildred and uncertain if he liked what he saw. She made him nervous. She still prayed, but there was a steely determination to it, and most of her prayers seemed focused on turning the children into suffragists, which he thought was nonsense. One day she told him she didn’t believe in God. She was baking a pie, deftly stripping early blueberries from their stems with a small knife to avoid staining her fingers. The fluted crust sat ready for the filling, next to the chipped green ceramic fruit bowl.

“Then what in heaven’s name are you doing praying!”

Why were pies always at the scene of family crises, he wondered.

My cherry trees come to mind and I rush outside again. Yes! The massive snowfall three weeks ago was so steady and straight-down and soft although wet that the blossoms stayed intact. Now it’s raining gently. Look at those berries!

I put it on my calendar: 10 June, bake a cherry pie. This gives me just enough time to consider who needs a pie the most, besides the baker.

I should have pointed out or at least created a link to Alexander Chee, who has written much about erasure, and the phrase about not participating in your own erasure comes from him. It can be a highly political act, and he writes about that. It can be a very private act, which I was referring to here, and there are so many shades in between, all of them causing enormous damage to all parties concerned. Never be tempted to do it for you will be a lesser human being, and if you are on the receiving end, be strong and be brave and do not under any circumstances participate in your own erasure. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/authors/profiles/article/78193-unmasking-erasure-alexander-chee.html

Hi Ellen, I liked this piece very much. Made me hungry too